Paris Plages – Turning a city street into a beach

Paris, no doubt about that, is one of the most beautiful cities in the world. Its charms have inspired poets, photographers and painters, musicians and lovers. Visitors come from all over the world to catch a glimpse of Parisian life. Reflecting the city’s attraction, rents are sky-high. Yet during the heat and humidity of summer, when tourist masses overrun the city, every Parisian who can afford to leaves the city for the countryside or the coast. Which means many have to stay within its confines.

In 2002, the office of the mayor of Paris decided to provide a relieve for this part of the populace. Since then, every July and August a 3.5 km stretch of the Voie George Pompidou, a road on the northern bank (Rive Droite) of the Seine that is heavily frquented at other times of the year, is blocked and temporarily converted to a beach. This means moving more than 5,000 tons of sand, hundreds of big umbrellas and palm trees, building playgrounds, dancefloors and bars.

The result is called ‘Paris Plages’ (Paris beaches) and provides a welcome refuge from the heat, humidity and tourist masses that have a firm hold on the city. The Paris Plages offer a sandy beach, music, dance, games for children and a romantic atmosphere for lovers. While cities around the world have come up with similar concepts, none of them can beat the atmosphere of a warm evening on that stretch of road that is borrowed from traffic for a few weeks in the sweltering heat of summer.

At full steam towards the Himalayas

Conceived and built during the British Raj, India’s railway lines are still the main arteries of the country’s traffic system. In hectic, overcrowded train stations travelers fight for space inside (or even on the roof of) one of the seemingly endless trains. Photographs of Mumbai’s Church Gate Station and Kolkata’s Howrah Station are symbols of overpopulation and the collapse of transportation infrastructure. Yet India’s railway system also offers an oasis of tranquility: the Darjeeling Himalayan Railway, affectionately called ‘toy train’ because of its diminutive track width of 2 ft., running from New Jalpaiguri to Darjeeling. Today, visitors come to Darjeeling for the famous four Ts: Tibetan temples, Tenzing Norgay (the sherpa who in 1953 together with Sir Edmund Hillary was the first to climb Mt. Everest and who later lived and worked here), the world-famous tea and the toy train.

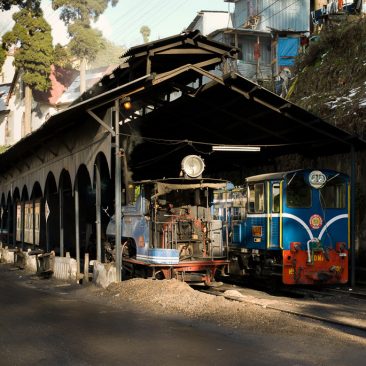

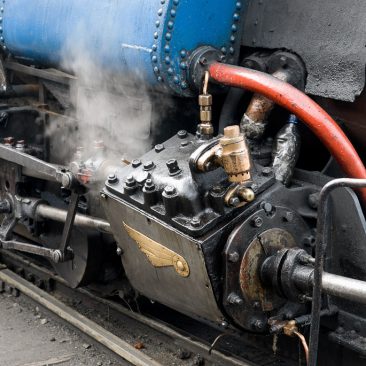

It's 5:30 a.m. in the small town of Kurseong, some 5,000 ft. up in the foothills of the Himalayas: a steam locomotive of the Darjeeling Himalayan Railway, the ‘Mountaineer’, is being prepared for the 20 mile trip to Darjeeling in the Loco Shed. The ‘Mountaineer’ was built in 1899 in Scottish Glasgow and has been chugging up the narrow tracks that link the plains of Bengal with the tea gardens of the foothills ever since. It’s cold and drizzling; some workers stand around an open coal fire in the Loco Shed, still shivering. The locomotive has already been fired up; the air is saturated with the smell of coal, steam and oil. For the trip ahead about 4,000 lbs. of coal are needed. Four workers load it into the engine’s reservoir using wicker baskets; nobody here seems to think of automation.

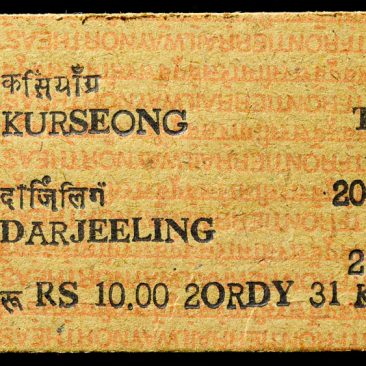

Some 20 minutes later: Heren T’khatri, Chief Ticketing Officer of the Darjeeling Himalayan Railway, patrols the platform and checks everybody’s tickets. The fare for the 20 mile ride in second class is ten rupees, about 20 US cents. Departure is at 6:00 a.m., right on time; according to the timetable Darjeeling will be reached in 2 ½ hours. The three tiny train cars carry an interesting mix of people: vendors who will sell their goods in the Darjeeling market, two railroad maintenance workers on their way to a repair site and, occupying the majority of the seats, young students. Along the railway there is a number of prestigious boarding schools dating back to the times of the British Raj, as their names still tell: St. Helens Convent, Goethals Memorial School, Dowhill Girls School and Victoria Boys School can be found here. The train is very popular with the students as it costs only a fraction of the bus ride.

Very slowly the train chugs through Kurseong’s ‘High Street’, passing so close to the stalls on the right-hand side that it would be easy to shoplift their wares by reaching out of the window. It’s still quiet in the streets, only at 10:00 a.m. the stores will open and the noise of the bazar will begin, not to end before late evening. The train line runs mostly parallel to the main road and crosses it frequently –there are 177 crossings altogether. At each and every one, the engine blows its whistle. Then there will be people or animals on or near the track, and the whistle will sound again. Once the train is on its way, night has ended for Kurseong’s inhabitants. In fact, people stand at roadside water taps, brushing their teeth.

Twenty minutes later the train stops for the first time. The hardwood sleepers of the 126 year old track have to be exchanged for more durable concrete ones, the track is blocked. After only a few minutes the train starts moving again - moving very slowly, coughing loudly and bellowing soot and coal filled plumes of steam and smoke. This is hardly a clean technology.

Not too long before the train has to stop again: the steam engine needs a water refill. While the tank is being filled, women from the village appear and offer hot chocolate-colored milk tea, the chai that is so popular everywhere in India, for sale. Especially the driver, the fireman and the two ‘sandmen’ who sit on the very front of the engine and drop sand onto the tracks to prevent excessive wheelslip at steep sections, are grateful customers of the invigorating early morning brew in today’s weather.

As soon as the train resumes its run to Darjeeling, the students begin to sing in a language that most Indians will not understand: it is Nepali, the dominant language here in the hills. A few miles later the clouds lift. On one side of the tracks the lowlands of Bangladesh come into view, on the other majestic Kangchenjunga, at 28,169 ft. the third-highest peak on earth, presents itself in the morning light. The Nepali song, the rhythm of the engine and the impression of being halfway between heaven and earth combine for an almost surreal experience.

At the steeper sections the train moves so slowly that it’s easy to hop off, walk alongside for a while and hop back on again. After more than 1 ½ hours only half of the distance has been covered and the train reaches the station of Sonada. Twenty minutes later it still hasn’t moved. Passengers become restless, some get off and continue with one of the many shared taxis. Someone asks the station manager for the reason of the delay: a landslide, caused by the heavy rains of the previous day, has blocked the tracks ahead. Nobody knows if they can be cleared today. The fireman keeps the engine on operating temperature, but of course he also doesn’t know when or even if the train can continue. The station manager calls the Darjeeling station over and over again, passengers ask policemen, who are equipped with two-way radios and should have real-time information on the progress of clearing the landslide, about the situation. One statement contradicts another: as soon as someone says the track has been cleared, another source claims the track won’t be usable before late evening. Meanwhile the first shared taxis return with the passengers who had left the stranded train earlier, now reporting that automobiles can’t pass the landslide, either.

The engineer of the locomotive takes it easy, warms himself on the boiler and exchanges the latest gossip with passers-by. Some boys collect small pieces of coal that have fallen from the engine. Delays like this are a fact of life on the Darjeeling Himalayan Railway; nothing to worry about, the train will start moving again a little later. But today the odds are against making it to Darjeeling. Two hours after the train arrived at Sonada the station manager declares that it will return to Kurseong. The return trip takes about as long as the journey uphill; altogether the train took more than six hours to cover 10 miles towards Darjeeling and back. The passengers who have to go to Darjeeling have no other choice but to spend another night in Kurseong and try again. For some it is an unpleasant interruption of their journey, for others, the chance to experience a fascinating part of railway history one more time.

Information

At the time of the raj, the British rule in India, hill stations were popular destinations to get away from the heat and the threat of malaria during the summer months. Not at all of them were easily accesible, though: the journey from Calcutta to Darjeeling took three days and involved trains, bullock carts and steam ferries. To improve this situation and to facilitate the transportation of the world-famous tea from the area, the government of British India decided in 1879 after brief deliberations to build a railway line connecting Darjeeling to Siliguri, 50 miles away and 6,600 ft. below. To save cost the line would not include tunnels, which meant that it would have to hug the terrain, necessitating steep climbs and very tight turns. Only a narrow gauge could be used and a width of 2 ft. was chosen. This narrow gauge invariably led to small-size rolling stock, giving rise to the moniker ‘toy train’. Operations started in September 1881.

Climbing up the Himalayan foothills in the toy train, a journey scheduled to take 6 ½ hours, but in reality usually closer to 10, evokes the feeling of that bygone era. The first part of the line leads through thick rainforest with beautiful sights of bougainvillea and orchids. Soon the track begins to slope upwards at a gradient of 1 in 20. At some sections it is even steeper; this is where loops and Z-type switchbacks were put into place. After a short climb the scenery changes again: now the train runs through tea plantations dotted with trees that provide shade for the delicate plants. In Tindharia the train passes the main depot and the workshop of the Darjeeling Himalayan Railway; this is where the old locomotives and cars are lovingly maintained. With the appropriate permit (available for a small fee) tourists can visit the workshop and get a notion of how much work is involved in keeping a 100+ year-old steam engine in shape. Even today most of the passenger trains are pulled by steam engines; the more modern Diesel engines are mainly used for freight trains. In 1999 the Darjeeling Himalayan Railway became a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Kurseong is the most significant town along the line and offers spectacular views: on one side of the train the view extends to the plains of Bangladesh, on the other side the peaks of the Himalayas come into view. In clear weather the third-tallest peak on earth, Kangchenjunga (28,169 ft.) can be seen from here. From Kurseong the train takes another two hours (if all goes well) to the highest point on the line, Ghoom. At 7,400 ft. this is the highest station in India and one of the highest in the world; only in the Andes of South America some stations are at higher altitudes. Ghoom is home to several very interesting Tibetan monateries, among them Samten Choling Monastery and Yiga Choling Monastery. The monks speak English and show visitors around the premises if their time permits.

From Ghoom the train slowly descends the last 5 miles into Darjeeling.The last section of the line extending from the passenger station into the bazar is no longer in use. The home of Tenzing Norgay, who climbed Mt. Everest together with Edmund Hillary on May 29, 1953 is on a hillside, a good kilometer before the station. Darjeeling's most famous sherpa later directed training at the Himalayan Mountaineering Institute (HMI) established by the Indian government in 1954. Located next to Darjeeling's beautiful zoo, HMI with its museum, showcasing equipment of many Mt. Everest expeditions, is well worth a visit, even more than a half century after the first ascent - a major world event in its day.

Moving India – The Hindustan Motors Ambassador

There are automobiles that have made history. Some did because they were fast, like the Ferraris and Porsches. Others because they represented the owner’s wealth, like those made by Bugatti and Rolls-Royce. There are those that are famous for their beautiful looks and those that have revolutionized automotive technology, like the Toyota Prius and the Tesla cars do now.

And then there are cars that have made history – because they were common. Cars that enabled the populations of entire countries to travel, to see places, to visit relatives, shedding the limitations imposed by railways and buses. The Ford Model T comes to mind, Italy’s Fiat 500, the French Citroen 2CV and, of course, the Volkswagen Beetle of my native Germany.

The second-most populous country on the planet, India, is home to an automobile that boasts a production span of 57 years. The Hindustan Motors Ambassador, a four-door sedan based on the British Morris Oxford Series III. Production started in 1957 in Uttarpara, West Bengal, not too far from Kolkata.

For many years, the Ambassador was the quintessential Indian car. It was ubiquitous in the cities, mainly in the form of taxis or, sporting a white exterior, as the typical government official’s means of transportation. It was a status symbol for private owners and an icon of dependability and national pride for the political caste. When I was photographing in Darjeeling in 2008, the governor of the state of West Bengal at the time, Gopalkrishna Gandhi, a grandson of the Mahatma, visited the city. He was driven there in a Mercedes, but made sure to change into an Ambassador a few miles before he could be seen. It was simply expected of him to arrive in the vehicle that had been known for more than half a century as the car that was moving India.

However, the success story of the Ambassador was not to be continued for long. Production had been going downhill since about the mid-1980s, when competition in the form of the Maruti Suzuki 800, a far more modern automobile, hit the Indian market. Also, more stringent emission standards proved to be a challenge for the technological base of the Ambassador. Eventually the assembly lines stopped on May 25, 2014.

And that may have been a good thing. When I visited the Uttarpara plant, conditions reminded me of the times of the industrial revolution. Assembly took place in a huge, dark building. There was no automation nor were there any safety measures to speak of. It simply looked like an almost 60 year-old industrial operation that had never been modernized. In the foundry, where the engine blocks were cast, workers handled the glowing, liquid metal withour protective clothing. The air was so bad that my assistant had to go outside after ten minutes.

Still, in a way it is sad that the days of the Ambassador are over and its numbers are dwindling. Hopefully some collectors will save a few cars, to be admired in another 57 years.

Singles: Stars and Stripes in Havana, Cuba

In the political realm, the relations between Cuba and the United States have been less than perfect for more than half a century. Since the Cuban revolution of 1959, tension and confrontation have become their defining qualities. Cuba is under an economic embargo of the U.S., and Americans wanting to visit the country have to work around travel restrictions. The rhetoric of Cuban leaders towards the country’s large northern neighbor has been less than friendly, to say the least.

The good news is that things look much brighter on the personal level. When I traveled to Cuba for the first time, the symbols of the revolution and the political system were everywhere. Portraits of Ernesto “Che” Guevara, the Cuban flag, and propaganda statements (“Socialismo o muerte”, socialism or death, being an example) can be found on the walls of many buildings. However, it soon became clear that these reflect the official side of things. For better or worse, many Cubans seem to cherish the emblems of the capitalist system, sometimes in the form of brand-name items, sometimes simply in the form of the national symbols.

This became especially clear one day when I walked the Malecón in Havana in the light of late afternoon. The Malecón is the 5-mile sea boulevard of the city. Ironically, it has been built by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, beginning in 1901. Today it is a place to hang out, walk along the seaside, take a dip in the water, listen to street musicians and meet friends. Right after I began my walk at the Castillo San Salvador de la Punta, I saw a group of young people playing and jumping into the water. One girl caught my eye, mainly due to the design of the bikini she wore. I had not expected Cubans to show the colors of a country considered an enemy by the political elite so openly. With the few words of Spanish I know I established contact and asked if I could photograph her. She agreed right away, so I grabbed my Leica and was rewarded with this picture.

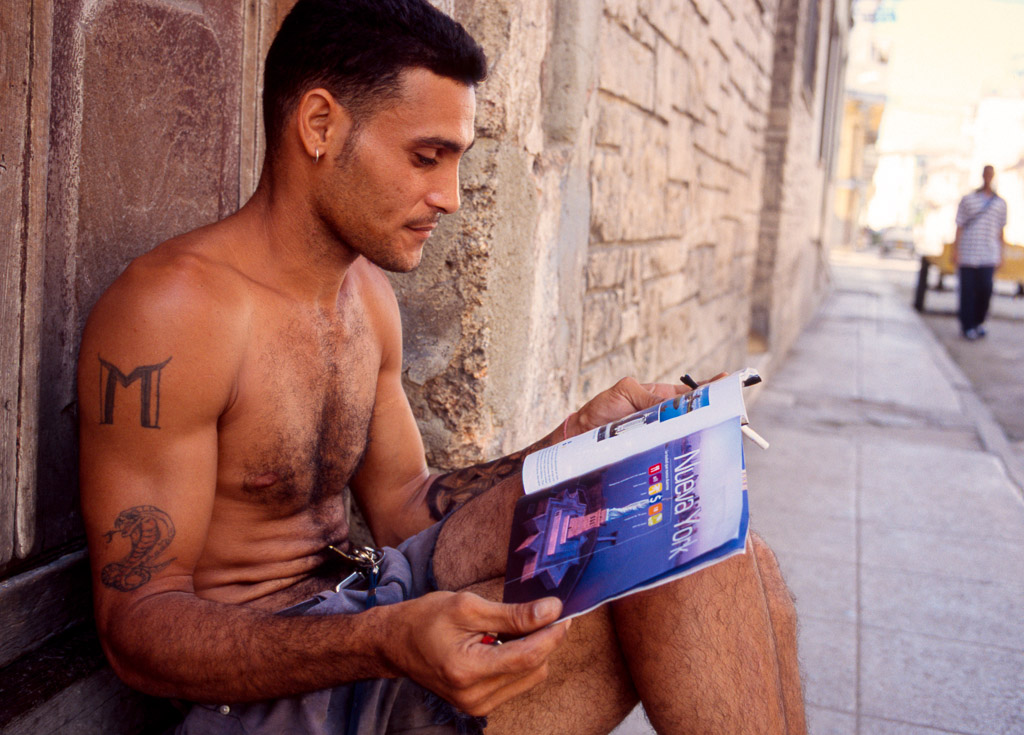

Later on, I discovered more and more fascination with life outside the country, and especially in the U.S., among young Cubans. This young gentleman was sitting in a doorway, studying a brochure advertising travels to places in America which had been given to him by a tourist.

Only time will tell if the allure of Western symbols is only superficial or if it will lead to a political and economic transition.

Demolition Derby in Shelby, MT

More than 40 years ago, I was a little boy then, my father would sometimes take me to an event where people deliberately did what was to be avoided in road traffic at all cost: run automobiles into each other with the intent of causing maximum damage. I remember how excited the audience was and how they cheered the last driver whose car still moved. For some reason events of this kind don't seem to take place in my native Germany any more.

Enter Shelby, a small town on the Hi-Line, a long stretch of road following the original railway tracks across northern Montana. This part of the world is dominated by highly efficient, large-scale farming and has a very low population density. Miles of road between towns. Not a lot of opportunities for entertainment. The annual Marias 4-County Fair is a big thing for anyone living here. And the main event on its last day, just before the closing fireworks, is that deliberate destruction of cars that I remember from my youth: the Demolition Derby.

For a fee of $75 drivers can enter the derby that offers the chance to win $2,500 for finishing in first place. There are a number of rules describing what types of cars can be run and what modifications are legal. Some cars make you wonder if they will run at all, others show the creative side of their owners.

The pit area is busy until the last minute before the first heat, as the individual runs are called. Fierce dogs watch over the cars.

As with any other sports event in the United States, the National Anthem is sung before the competition begins. Audrey Cheetham, 12 years old, captures the audience with her clear voice as her father, dressed for the occasion, works the PA system.

With the cars of the first heat caught up in a jumble of steel, the announcer gets really excited.

Some cars can leave the arena on their own, others need help.

In between heats, repairs are allowed for a limited timeframe, resulting in a frenzy of activities in the pits.

Close to the end of the event, only three cars survive.

An evening of quality entertainment and a good place to pick up some scrap metal.

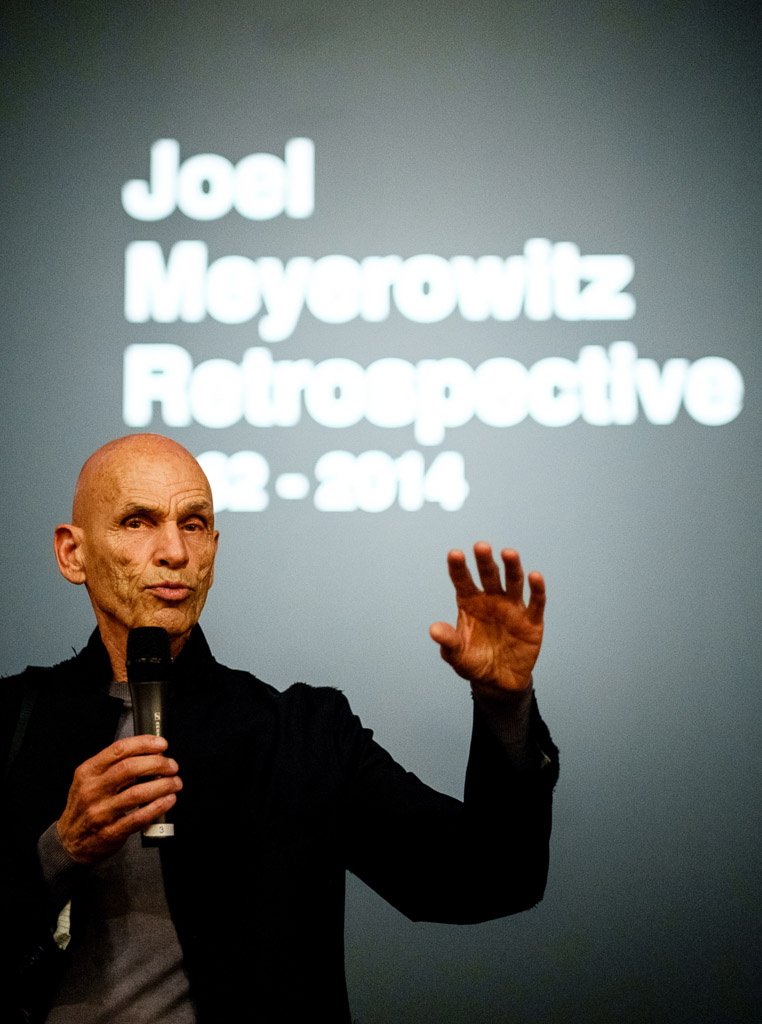

Joel Meyerowitz retrospective in Düsseldorf

It was in June of 1994. I was in New York City for a few weeks, shooting on the streets and trying to capture the atmosphere of this fascinating place. Shortly before the trip, my late friend Günter Wehrmann had told me about a book on street photography: Bystander: A History of Street Photography by Colin Westerbeck and Joel Meyerowitz. As soon as I arrived I hunted down a copy of the book (there was no instant availability through places like Amazon in 1994) at A Photographer’s Place, a book store specializing in photographic literature. Every night after coming back to my hotel from my own efforts at street photography, I continued reading this book until I fell asleep.

Joel Meyerowitz is not just a scholar or critic of street photography. He is one of the masters of the genre himself. Back in the 1960s he roamed the streets of New York City with Garry Winogrand, Diane Arbus, Lee Friedlander and others. While Winogrand is best known for his black and white work, although he certainly didn’t ignore color, Meyerowitz completely switched to color film pretty soon. Compared to Winogrand, his work is less gritty and in-your-face, but often has a humorous twist to it.

While color is an important factor in most of his street photography, later on Meyerowitz made it the central element of his pictures. His 1978 book Cape Light is one of the classics of color photography.

Right after 9/11, Meyerowitz got access to the area around Ground Zero. His pictures, published in the book Aftermath, are testament to the devastation brought on by the attacks.

Last week I finally met Joel Meyerowitz in person at the opening of his show “Joel Meyerowitz – Retrospektive 1962 - 2014” at the NRW Forum in Düsseldorf, Germany. The show encompasses all the different areas he worked in, from early street photography to his Cape Light pictures, on to portraits and the Aftermath body of work. It will be open until January 11, 2015 and is definitely worth a visit.

Speaking to Joel about his work and about why we have to wait this long for the trade edition of his two-volume book Taking my time (the book is true to its title: I ordered mine through Amazon in January of 2013 and still get notices about further delays; however some of the 1.500 copies of the deluxe edition are still available) was very enlightening. His wonderful wife, Maggie Barrett, accompanied him to the opening, and she was no less interesting to talk to than him. Having been a dancer, an acress, a playwright and a novelist, her life is as varied as Joel’s photographic oeuvre.

So, if you come to Düsseldorf before January 2015, make sure to stop by at the NRW Forum.

Thomas Höpker in Cologne

“For the most part it’s your fault”, I said, at the same time smiling at the gentleman vis-à-vis. He tilted his head and gave me a questioning look. “That I became interested in photography is for the most part your fault”, I explained.

It was Thomas Hoepker I was talking to. He is one of the most influential German photojournalists of the last fifty years. When I was a little boy, Hoepker worked for STERN, then the magazine with the highest circulation in my country. As my family didn’t have the means to travel a lot, my mother and I would read all the articles they published about life in different places of the world with great interest. Many of these articles were illustrated with pictures by Thomas Hoepker.

In 1976 he and his wife Eva Windmoeller, who also was a journalist, moved to New York City where he worked as a correspondent for STERN. It’s safe to say that he had significant influence on my picture of the United States. Later on he became Director of Photography at the American edition of GEO. In 1989 he joined Magnum Photos and was the agency’s president from 2003 o 2006.

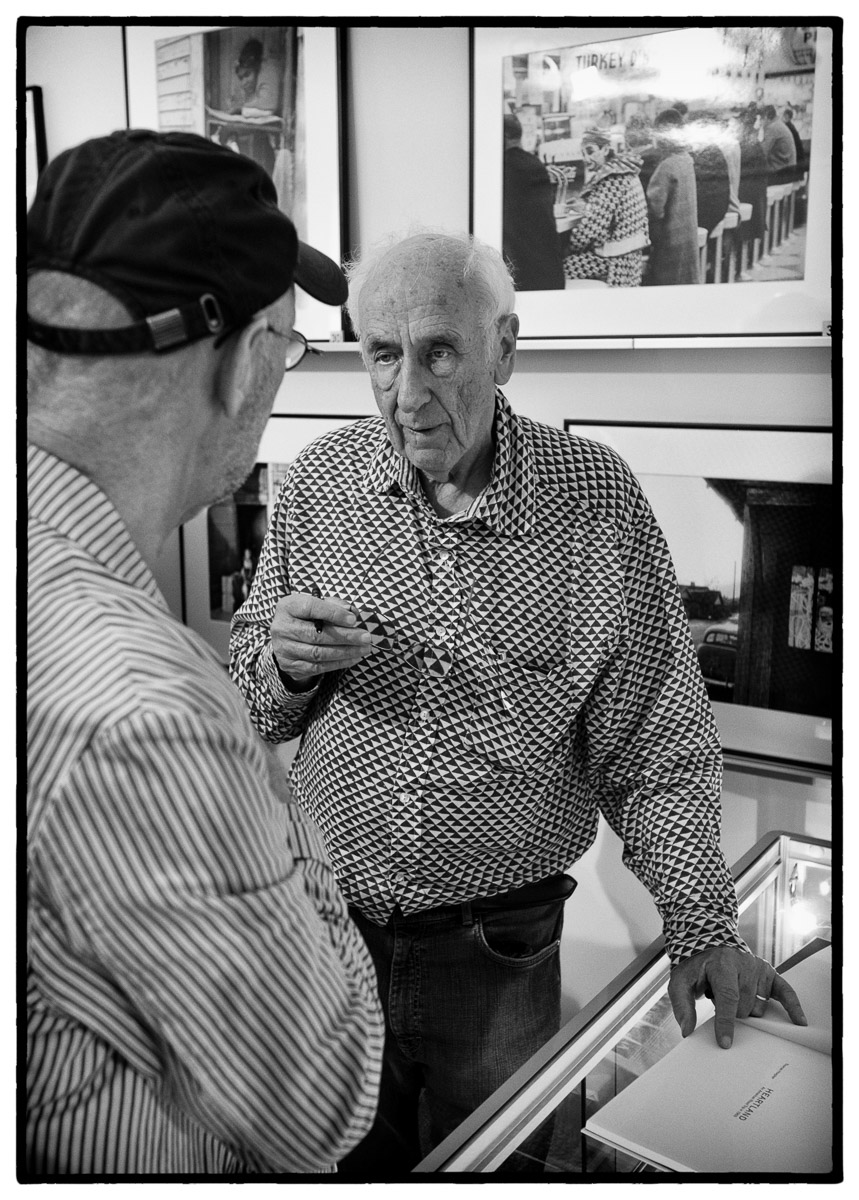

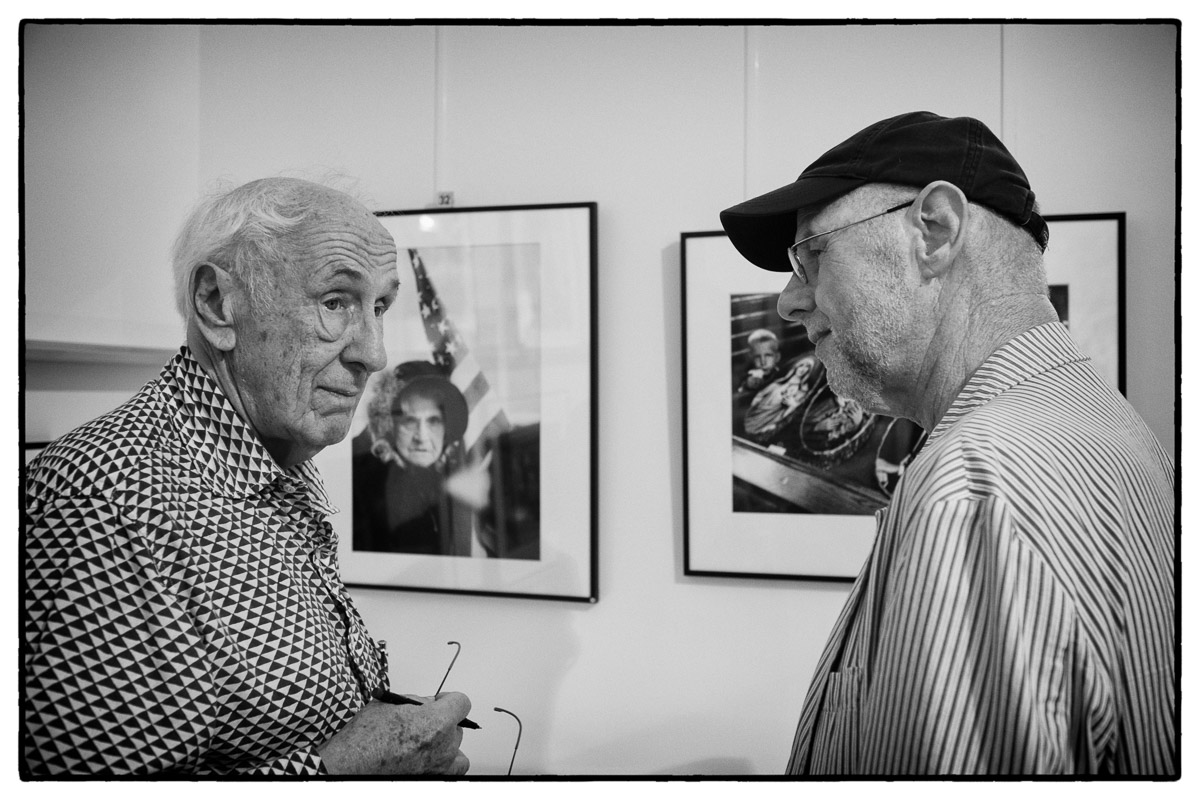

In September of 2014, thirty years later, I was talking to him at a small photo gallery in Cologne, in focus Galerie. The gallery showed his exhibition “In Amerika – 1963-2013” and he was there to sign his books. At age 78 he still has an impressive presence.

Hoepker was fortunate insofar that he got to travel to the United States in 1963, when his employer at the time, the German magazine Kristall, sent him and a writer to travel the country for three months. His pictures from the trip clearly show the influence of Robert Frank, who had published his book The Americans just five years earlier.

Following this story he began to travel around the globe. Yet he always returned to the U.S., where he photographed a number of essays, the most famous of which is about Muhammad Ali. Eventually he produced a book on Ali, Champ.

Hoepker was in New York City when the 9/11 attacks happened. One of the pictures he took that day became iconic. You can see it here.

His latest book just hit the market. Wanderlust is a retrospective of his long career. Its strength, showing pictures from a multitude of locations and situations, is also its weakness. Personally, I would have enjoyed a more structured approach, maybe with chapters dedicated to certain subjects or ideas. Yet for anyone looking for a comprehensive presentation of Thomas Hoepker’s work, this book is a must-have.

Sustainable farming in Montana

A few days ago I wrote about large-scale farming in northern Montana, a highly automated operation that is reminiscent of industrial manufacturing processes. Hi-tech machinery, complex chemistry and advanced breeds of grain are necessary ingredients of this kind of agribusiness. What you can see there is the result of a long process of optimization for one specific goal, the yield per acre.

Yet productivity and efficiency are only a part of the equation. Our dietary requirements go far beyond having “enough” to eat. We are looking for healthy foods, free of potentially dangerous chemicals, that taste good and can be grown in a way that leaves the land intact. Enter the world of sustainable agriculture.

“Sustainable” is not a single, precisely defined way of farming. The word describes the common aspect of a multitude of approaches, something that has been defined as “economically viable, environmentally sound, and socially acceptable”.

Traveling throughout Montana I was lucky to meet the operators of a farm that tries to accomplish just that. Victoria Werner and her partner Elan Love run Deluge Farm, a small outfit on Camas Prairie that sticks to the principles of organic farming. At only twenty acres it is diminishingly small compared to the industrial-size farms on the Hi-Line that I wrote about in the previous post. Only a little over an acre is used for growing vegetables, the rest is reserved for raising sheep, chickens and turkey.

When they moved from Ohio, where they had studied at Oberlin College, to Montana, Victoria and Elan brought lots of enthusiasm – and very little experience in organic farming. They asked local farmers about the conditions of the soil and about irrigation. They bought books and searched the Internet for information and tips. Keeping cost down (their only help is a few students who spend the summer on the farm in return for room and board) and living frugally, they now manage to get by on the farm’s revenue after a few hard years.

On Deluge Farm, there is no heavy machinery. The plants grown here get touched only by human hands. Some of vegetables grow out in the open, some in a greenhouse that Elan designed and built himself. However, not all experiments turn out well. Early on, Victoria and Elan built a cold storage room that was insulated with wool from their own sheep. Seemed like a great idea: cheap, good insulation (nature-proven, so to speak), recyclable and locally grown. It turned that all kinds of bugs also liked the coziness of this kind of insulation. Eventually they had to replace the wool by sheets of styrofoam.

Besides growing produce, small farms like this face another problem: distribution. Whatever grows on Deluge Farm is sold by Victoria and Elan on farmers’ markets. The market in Hot Springs is the closest one at a distance of about 17 miles. It’s a small market with only a few customers, and due the generally meager incomes of Hot Springs residents prices are low. The farmers’ market in Missoula is far more attractive in both volume sold and prices. Yet it is 80 miles away, meaning three hours of driving back and forth. While it is ecomically viable to sell there, it certainly isn’t in terms of enviromental impact, even though they use a hybrid engine car for the ride. Large-scale farms with their highly optimized delivery systems are at an advantage in this respect.

The issue is how to combine the advantages of high-yield, industrial farming with those of small-scale, sustainable methods. Even agriculture, which has developed more than 10,000 years ago in the Fertile Crescent of Western Asia, leaves some questions open today.

Harvest on Montana’s Hi-Line

“Five hundred”, Jason Wanken said. “OK, and the price?”, I asked. Again the reply was “Five hundred”. I was sitting in the buddy seat of a combine that had a 500 hp engine and cost around US$ 500,000. An impressive machine that replaces hundreds of farmhands.

Up here on Montana’s Hi-Line, the stretch of land around the Great Northern Railway line, bigger is better. When settlers were lured here in the early 20th century, they could claim up to 320 acres in exchange for farming the land for three years and building a house. Soon it became clear that this wasn’t enough to feed a family, and a process of concentration set in. Today, the average farm size is more than 3,000 acres.

Wanken’s family farms some 5,000 acres, most of it wheat. He and his brother own three big combines, which allows for quick harvests at just the right time and gives them enough capacity to do some custom cutting in addition to harvesting their own crop. The downside is that all the equipment they have binds a lot of capital.

The ride in the combine was actually quite comfortable. Air-conditioning, a filter system against the outside dust, noise insulation and a nice stereo system help create a relaxed atmosphere. So does the computer that controls the machine. With the help of a GPS receiver it automatically steers the combine to within a foot, so there will be no overlap between tracks and no wheat will be left uncut. I have seen some farmers who got so bored on their combines that they played with their cell phones all the time, texting friends and family. Every time the grain tank is full a semi truck drives alongside the combine and the grain is unloaded while the cutting continues.

This process is so efficient that a farmer can run a 5,000 acre farm with only the occasional help of his wife and a truck driver at harvest time. As a consequence, there are not many farm jobs left, which is one of the reasons young people are leaving the area. Towns like Shelby, Chester, Inverness and Rudyard suffer from declining populations. Some of the towns were forced to consolidate their schools as the diminishing numbers of students didn’t justify individual ones any more.

While it was customary to grow wheat in a field one year and then let it lie dormant for the next, crop rotation or crop sequencing is gaining traction among Hi-Line farmers. Especially field peas and lentils have proven to put nitrogen back into the soil and break the lifecycle of wheat pathogens, insects and weeds. Columbia Grain International (CGI) operates a highly automated plant in Tiber where peas and lentils are cleaned, sorted and packaged ready for shipment by train.

The railway that originally made the Hi-Line what it is proves to be a limiting factor today. For long stretches it only has a single track, making it hard to manage trains of different speeds or directions. In the mountainous western part of the line that eventually goes to Portland and Seattle, a long tunnel that needs to be ventilated for three quarters of an hour between train passes is a severe bottleneck. Most of the limited capacity of this railway system is used by long rows of freight cars that carry oil and natural gas from the Bakken Shale, a highly productive deposit in North Dakota and the eastern part of Montana, to the West Coast. Says Mike Backen, who manages the CGI pea and lentil plant,”Often when I order twenty railway cars for our products, I get only three. The oil companies simply pay much more than we can”.

A major factor in assessing the price of a crop, be it wheat, barley, lentils, peas or any other, is its quality. Quality can be determined by many factors, including the amount of mechanical damage (for example by hard rain or hail), the amount of weed seeds contained in the harvest and the content of nutrients. The Montana State Grain Lab in Great Falls is the officially licensed testing facility in the state. Farmers and trading companies have their crop analyzed here, as well as insurance companies to validate crop damage related claims. A group of experts perform a multitude of tests, ranging from measuring protein content and falling numbers of wheat to determining the percentage of damaged peas in a shipment.

A lot of us don't know anymore where our food comes from and how it is processed. Seeing firsthand how much science, technology, money and effort go into producing something as seemingly simple as bread was eye-opening and fascinating.

Singles: Looking back at the Twin Towers

Today, exactly thirteen years after the attacks on New York City's World Trade Center, I remembered a photo I took in 1994. It was a beautiful June day and I was on the Staten Island Ferry, mainly to enjoy the view of this vibrant and exciting city.

While the ferry was pulling away from Manhattan, I noticed a young man leaning on the railing, glancing back at the island in a contemplative mood. I quickly raised my Leica, set the aperture so the background would be out of focus yet still showing enough detail to be recognizable, and tripped the shutter.

Seven years later, the tragic events of 9/11 changed the meaning of that picture forever.